Learning to love myself first

Special Valentine’s Edition ❤️—the process of becoming my own advocate & what doing so has unlocked

There is so much to navigate when you have a medical problem: the crappy symptoms of the thing at hand (ugh, back pain), understanding who to consult, meeting with them, digesting the information, deciding which treatment path to take, and of course, the side effects of said path. For systemic health issues like mine, lather, rinse and repeat this process at least 20 times. Now do this on top of all of life’s other demands (and joys!) like work, family, and community. And try and keep your mental and physical health in a state of harmony. I’m le tired.

I just want to trust the experts; let them decide

Over the past 10 years, I’ve tried to streamline this process as much as possible. Reduce the number of people and institutions involved, trust the experts, follow their advice. My dad, not wanting to see his daughter suffer, has pushed for going to Stanford, MD Anderson, even a hospital in Chile, and frequently gets lost in the internet rabbit-hole researching Bee Pollen for cancer cures. Repeatedly I have resisted. I didn’t want cancer to take over my life. I wanted it in the background. That mole you know you should get checked out but will wait another month.

By removing work in December, I began to be present. To put myself first. To look back on my journey, and more importantly, to take stock on the advances the medical industry have made with cancer and Desmoid Tumors. The trials and research. Organizations that were doing things differently.

Being guided to a new paradigm

“When the student is ready the teacher will appear.” —Tao Te Ching

I revisited Leila Janah’s story, the founder of Samasource who tragically and suddenly passed away from a rare sarcoma last year. I found an article about her working with an organization called Research to the People that does patient advocacy and helps organize a “hackathon” of sorts with researchers, doctors, and scientists to help find treatments and cures for difficult medical cases. Right now patient data lives in silos in institutions (case in point: I still have to physically mail a CD to Ohio State University after every MRI). The theory is that if the data is open and shared across organizations, new insights and treatments could emerge that helps both the patient but also the medical industry at large. They were looking for collaborators for 2021. I applied.

Pete, the founder, responded to my Google Form about an hour later, at 8pm on a Sunday. This was already feeling like a different experience of the medical system I’d become so apathetic to. He mentioned he would be in the Bay Area soon, and we could go on a social-distanced hike or bike ride.

Speaking in a language that felt familiar, Pete taught me about the advances in genome sequencing, about the importance of knowing the cellular makeup of what is making my tumor grow, what would motivate doctors to get involved in my case, and the best institutions to partner with. He recommended a book, The Gene, and I started watching documentaries and going down my own gene rabbit-hole.

I began to open up to the curiosity of Ursula. And feeling equipped to have scientific conversations that once bewildered and overwhelmed me.

Developing the mental models to navigate the process

The thing was, I’ve done genetic testing on Ursula, multiple times. After my surgery in 2018, Ohio sent my tumor in for sequencing to the National Cancer Institute. They didn’t find the traditional markers of a Desmoid Tumor, so they tested it again, with no results. Last year, we ran a FISH test to look for one specific EGFR gene mutation, which could point to a targeted treatment. But this also was inconclusive. My oncologist at Ohio told me, “it looks like a Desmoid and smells like a Desmoid, but we can’t find anything to genetically link it to a Desmoid.”

The doctors hadn’t been able to find anything, and I assumed it would be a mystery until the sequencing got more advanced. They are the experts. I guess we wait.

Now, with Pete as my guide, I was shimmying over into the driver’s seat. I was developing the mental models to own the process. I wasn’t asking the doctors for what to do next. I was gathering the research and information to ask the right questions, to the right people, at the right time.

I started talking to my friends about this great guy Pete, about this great organization. A friend introduced me to a sequencing company he invested in, which led me to connect with the Make an Impact team at Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK). They decided to take on my case. For life. For free (they don’t even have my insurance information). MSK has a team of 8 Sarcoma Oncologists (including two that specialize in Desmoids). UCSF has 1. As part of the process, they perform a proprietary sequencing test looking at 500-600 genes linked to typical cancer treatment options. I was elated!

Soon I was collecting tubes of blood, embraced by a mini ice pack, and FedExing them to New York. MSK informed me that the FISH test had a TMB ratio of less than 1. Meaning that likely the $700 test I paid for out of pocket didn’t have the genetic information needed on the slide. So it wasn’t that I did or didn’t have the EGFR mutation. It was that the slides sent didn’t have enough information to know either way.

The biggest difference is knowing which questions to ask

Pete taught me that while the MSK test was great, whole genome sequencing is the holy grail—and not all sequencing technologies are equal. Long read has certain advantages for rare cases and the data library that they pair it with after the sequencing is what distinguishes between sand and gold.

He said I should ask if my tumor was “fresh frozen” at Ohio or consider a new biopsy. Whole genome sequencing can only be done on live tissue.

I got into a long discussion with my doctor at MSK about getting a biopsy and whether my tissue had been fresh frozen at Ohio. My doctor got excited—if it was frozen “alive”, we could do whole genome sequencing, for free, without another operation.

Ohio responded that yes, the tumor was frozen in nitrogen, but it was deidentified and they were unsure if it could be reversed. After a little research, they were able to find my sample and a whole new data possibility emerged!

The tests are now in process and Research to the People officially accepted me into their program. We’re going to start generating additional data, and will be inviting more researchers to see what they can find! I have no idea what the outcome will be, but I do know that I’m headed down a path, that if successful, would be the first time in 10 years a treatment could be decided for my tumor.

This was only possible for me by creating space to learn more about the issue, having a guide to point me in the right direction, developing the mental models to navigate the process, and shifting into a new paradigm.

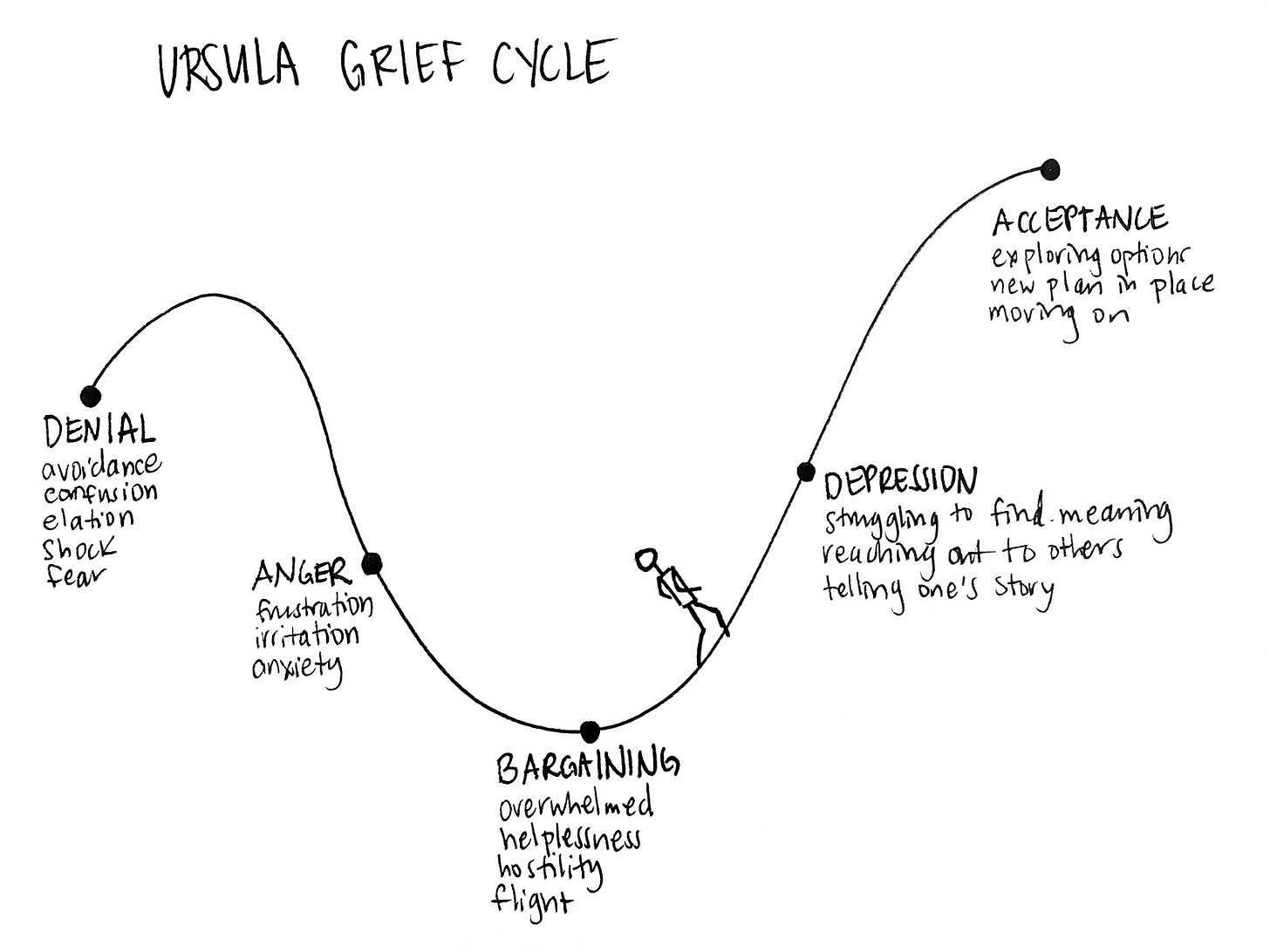

Upon reflection, I believe this mindset is only possible if you're nearing the last stage of the grief cycle. If you are stuck in denial, depression, or bargaining, I imagine you’d lack the clarity to know what to do next.

Finding a state of equanimity with Ursula

I am loving myself first by becoming my own advocate. I have found a state of equanimity with Ursula, the still point between effort and ease. I’ve learned it is important to be proactive with things like health but also let the process unfold as it does. I can’t stress about every nerve flare or new area of growth—this is simply outside of my control. I choose to focus my energy on my path, where I am going, keeping a pulse on the research, and surrounding myself with an amazing team.

While you can’t fully outsource what matters most to you, you can love yourself first, prioritize yourself, and let others love you as well.

You are loved. Happy Valentine’s Day.

Gratitude to my friend Jeanette Mellinger, for helping me sense-make my learnings on self-love and for our weekly creative writing sessions that make continuing this blog possible.

You are so amazing. Happy Valentine's Day sweetie

this is amazing!! thank you Vanessa for sharing!